Aaron Curry & Richard Hawkins:

If you are the type who likes to go on those crazy, dizzying rides at the county fair, or who craves pale orange circus peanut candies; if you get a thrill out of the wood-grained cardboard, prefab “Troll Shanty Shack” of the 60s, where the furnishings are printed right on the walls; if you love the two-dimensional esthetic of the Flintstones, you have come to the right place. Cornfabulation by Aaron Curry and Richard Hawkins’ collaborative exhibition is currently showing at the David Kordansky Gallery in Los Angeles. Should you also happen to delight in the look of Japanese grocery packaging and gravitate toward colors like watermelon pink and citron green, look no further, simply enter the amusement park of neon-colored, wood-grain patterned walls whose surface literally changes state before your unbelieving eyes, context-shifting between being architecture, a picture frame, a window, finally escaping it’s role as wall covering altogether, breaking off into flat fragments, regrouping, criss-crossing these fragments to stand alone as fully realized sculptures. But the amusements in this odd park don’t stop with the walls morphing into sculptures.

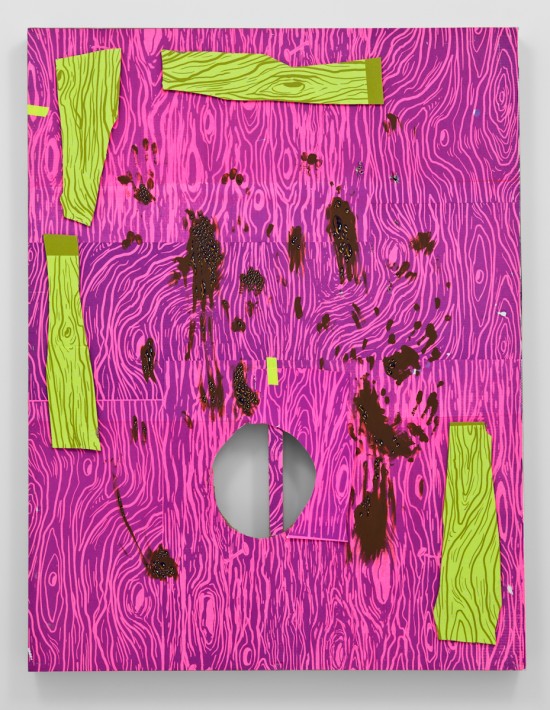

Aaron Curry, Untitled, (2011), silkscreen, tape, gouache on cardboard and paper with rope, 60.5 x 46.75 x 3.5 in

Not so, here. One cannot begin to talk about the Curry-Hawkins exhibit without describing the all-important wallpaper. At once architectural, transient, cheap and purposefully temporary, the panels are made of wood-grain patterned cardboard, bolted onto the walls throughout the exhibit. These large panels with their repeated pattern of wood-grain, in two-tone shades of neon green and pink, acid purple and citron, form a large scale patchwork quilt throughout the rooms, evoking the sensibility of the TV show Green Acres, or the fabric from a dress that a big-eyed girl in a Keene painting would wear. Serving as a background that does anything but remain in the background, at times morphing into three-dimensional sculpture, popping out of the walls in the form of crazy picture frames and even reorganizing as windows complete with mullions made of the stuff. Of note is the appearance of two dimensional representations of tacks or nails amidst the wood-grain pattern – as in Greenberg’s essay: Collage, a reference to that deeply forgotten surface where art used to take place throughout most of history.

Aaron Curry, Untitled (detail), (2011), silkscreen and gouache on cardboard, 60.5 x 46.75 x 3.5 in

There are three rooms in the exhibit, each representing a stage of the artist’s collaboration, the first room is a civilized standoff between the two styles, the second might be considered an outright declaration of war, and the third…well, you be the judge.

Richard Hawkins, 13 Crypts (#6), (2011), collage, acrylic and cardboard on wood, 32 x 25 in

Richard Hawkins’ series of collages titled 13 Crypts is displayed on two-tiered shelves. These light, colorful collages float on the surface of shallow boxes painted to look like they are covered with metal plates attached by rivets, the style of which evokes a child’s cardboard castle more than any real dungeon. The delicate watercolor-collage technique consists of a combination of water color shapes and cut outs of beautiful young Asian men. Just as you are feeling happy and content looking at this delightful series of images, you are confronted by something else entirely.

Aaron Curry and Richard Hawkins, Trophy, pink, (2011), acrylic on rubber mask with wire on board, silkscreen on cardboard, 32.5 x 28.25 x 3 in

“Herb got my wig fried like a bad perm…” – Wu Tang Clan

One might substitute the word Art for herb here – because there are scalps in these frames. Yes, inside out heads, hair streaming, unkempt from underneath. No blood thankfully, but rather a jumble of smeared colors in the center of the scalp – no need to take art in, your scalp has already done that for you, and here it is on display – or at least an example of it. Underneath all this, the hair, the scalp, is the art experience in the brain actually showing! And still inside the frame, there is more: colorful, primitively painted target of crude, concentric circles, off center, askew to the scalp. Hmmm.

Meanwhile what about the frames themselves? The walls have slyly pushed themselves out into sharply angled picture frames, with off-kilter cartoon-like dimensions plucked straight out of the Jetsons.

And while that was going on, the sculptures have already started to form, pinching themselves off from the frames and crawling across the gallery floor to reassemble, all of this happening while you were distracted by the colorful scalps and targets. Again, when you weren’t looking, the dungeon-themed collage frames have gotten into the act, two of them expanding into boxes that are now pedestals for the sculptures. Never a dull moment.

Room #2

Something has gone terribly wrong. Nothing is stable, boundaries between walls and frames, between frames and their content, have dissolved, color has escaped from pattern, shapes are falling out of surfaces, literally hanging by a thread, or tenuously attached by a tab of flimsy masking tape. Sides of frames have crawled around onto the front, competing for attention as content. Holes are cut in panels – making us realize that a frame is basically anything that is pierced in some way. One panel divides itself into 4 sections and becomes a window, while a window mullion can be seen peeking out from a sawed out circular hole of another.

Aron Curry, Untitled, (2011), silkscreen and gouache on cardboard, 60.5 x 46.75 x 3.5 in

Aaron Curry, Untitled (detail), (2011), silkscreen and gauache on cardboard on paper, 60.5 x 46.75 in

Yet another panel seems to be sweating brown condensations, surreal beads of liquid are forming on the surface. Thank god that went no further – who knows what might have evolved. Where before there were dungeon boxes, white I-beams now support these sculptures, perhaps in a nod to architecture, the next logical stage of further three-dimensionality.

Room #3

Perhaps the most disturbing and dramatic. A sense of unavoidable horror must be confronted here, when we come face to face with the unthinkable: a single, frightful square column has risen up out of the center of the floor, covered in a small scale version of the neon patchwork pattern (lest we forget from whence it came), and atop it, there is an ominous looking shoebox.

You don’t want to look in it, but you feel somehow strangely driven to do so. Inside. The bits and pieces that are called: Karen Black Forever. You want to look away, but you cannot: a pile of shredded rubber, brutally sliced into ribbons, a barely visible wisp of black hair, just in case we weren’t sure, and most horrible of all, three small, undecipherable, notes, each one attached to that forsaken pile of who knows what, with the cruel and simple paperclip.

Aaron Curry and Richard Hawkins, Karen Black Forever (detail), (2011), rubber mask, acrylic, paper, paperclips, shoebox and cardboard on wood, 54 x 17.25 x 13.25 in

The notes are covered in brushstrokes of watery black ink. The eye begs to see a pattern, to read an explanation into the blurry markings, or to at least find a curious, if obscure, miniature Chinese landscape within these cryptic notes, but no such relief is forthcoming. On the outside of the shoebox, “Forever”, is stamped in silver hologram, and a lyrical cursive font. The style is Karen, the color is black, the size is 6, but we will never, ever, know or understand her. Once we have come to terms with the deconstruction of an identity to the point of fitting into a shoebox — we can continue on with life (and the exhibit).

Aaron Curry and Richard Hawkins, Alistair McOdetoo #6 (detail), (2011), mixed media and silkscreen on cardboard, collage, 42 x 34 in

In this room, the frames have all but disappeared, leaving behind only colorless, floating, neutral containers within which the delicate collage-paintings must coexist alongside the very aggressive neon wallpaper which has staked out a central position the inside the nonexistent frame. Miraculously, after the dangerous boundary-crossing wars of the second room, both collage and wallpaper have survived. The wallpaper, still ferocious but now lying down, like an obedient hound, and the collage-paintings having stood their ground and emerged intact, their delicious candy colors, beautiful, nearly naked young Asian men cut-outs, their conveyance of leisure time, the possibility or impossibility of sexual, even romantic dalliances – are alive and well. But wait a minute, something has happened. Another element has crept in. Floating, bleeding, decapitated Zombie heads hover near the young bodies and a tri-colored trash barrel has appeared.

Aaron Curry and Richard Hawkins, Alistair McOdetoo #1 (detail), mixed media and silkscreen on cardboard, left collage, 42 x 34 in

Aaron Curry and Richard Hawkins, Alistair McOdetoo #5 (detail), (2011), mixed media and silkscreen on cardboard, collage, 36.5 x 28.5 in

In the end, it seems that everything has more or less survived the melding and tearing apart, the war of elements and dimensions and finally, the Asian boys and Zombies must get along, they must share their space with the rainbow colors and the fierce wallpaper. And the frames? Well maybe they are not so important after all, maybe they are just artificial boundaries that help us forget the terror and the turmoil that happens when things breaks down. The sculptures are another story, they seem to have all but disappeared, except for the great sadness that is Karen Black Forever and must be gotten over somehow.

Aaron Curry and Richard Hawkins, Karen Black Forever (detail), (2011), rubber mask, acrylic, paper, paperclips, shoebox and cardboard on wood, 54 x 17.25 x 13.25

Finally, as you wander, visually shell-shocked, back to the parking lot and your former life, you are aware, that somehow, through it all, Aaron Curry and Richard Hawkins’ Cornfabulation not only survives, but triumphs as a collaboration; coherent and incoherent at turns, agreeing to disagree with itself. You might feel a bit sick and dizzy, and certainly exhausted, but also exhilarated – as you should after a thrilling visit to any amusement park.

Aaron Curry & Richard Hawkins Cornfabulation at David Kordansky Gallery

Portia Iversen is a Los Angeles eclecticist whose interests include the visual arts and writing, as well as neuroscience. Besides winning an Emmy Award for art direction, she worked as a TV writer, and founded a nonprofit foundation for autism research. Iversen also published a book in 2007, (Strange Son, Riverhead Press). Her latest interest is writing about art.

Portia Iversen is a Los Angeles eclecticist whose interests include the visual arts and writing, as well as neuroscience. Besides winning an Emmy Award for art direction, she worked as a TV writer, and founded a nonprofit foundation for autism research. Iversen also published a book in 2007, (Strange Son, Riverhead Press). Her latest interest is writing about art.

Leave a Reply